…from the Pre- to Recent History tour

of Central Nevada and Utah

In a short 75-year span from 1850

through the late 1920s, we’d gone from walking across the continent to flying

across it. While it once took

months to get a letter from the gold fields in California back to the farm in

Illinois, by 1925, it could be accomplished in 29 hours using the airmail

service.

I suspect that this advanced delivery system came into being

because after World War I there were many skilled pilots with equipment

available and time on their hands.

Prior to the advent of radio wave communication, pilots

could only rely on visual cues to get from place to place. Thus, the early air service

followed the railroad across the otherwise trackless deserts of the Basin and

Range.

Across Utah and Nevada, remnants of some concrete arrows may

be found. These were coupled with forty-foot tall light beacons. Each beacon had a gasoline generated power plant to supply the necessary electricity for the light. The illuminated arrows were

placed across the desert to route the early flyboys of the mail service without requiring visual contact with the rail line. Some remnants are accessible

along the I-80 corridor. Some are

further afield.

Recently, we found a few.

This one is nicely preserved located within the I-80 right-of-way.

Others are being overtaken by weather and weeds.

Some required access through a gate.

This example shows an angle, as it is located at a point

where pilots must change their heading.

The steel remnants used to anchor a forty-foot tall beacon.

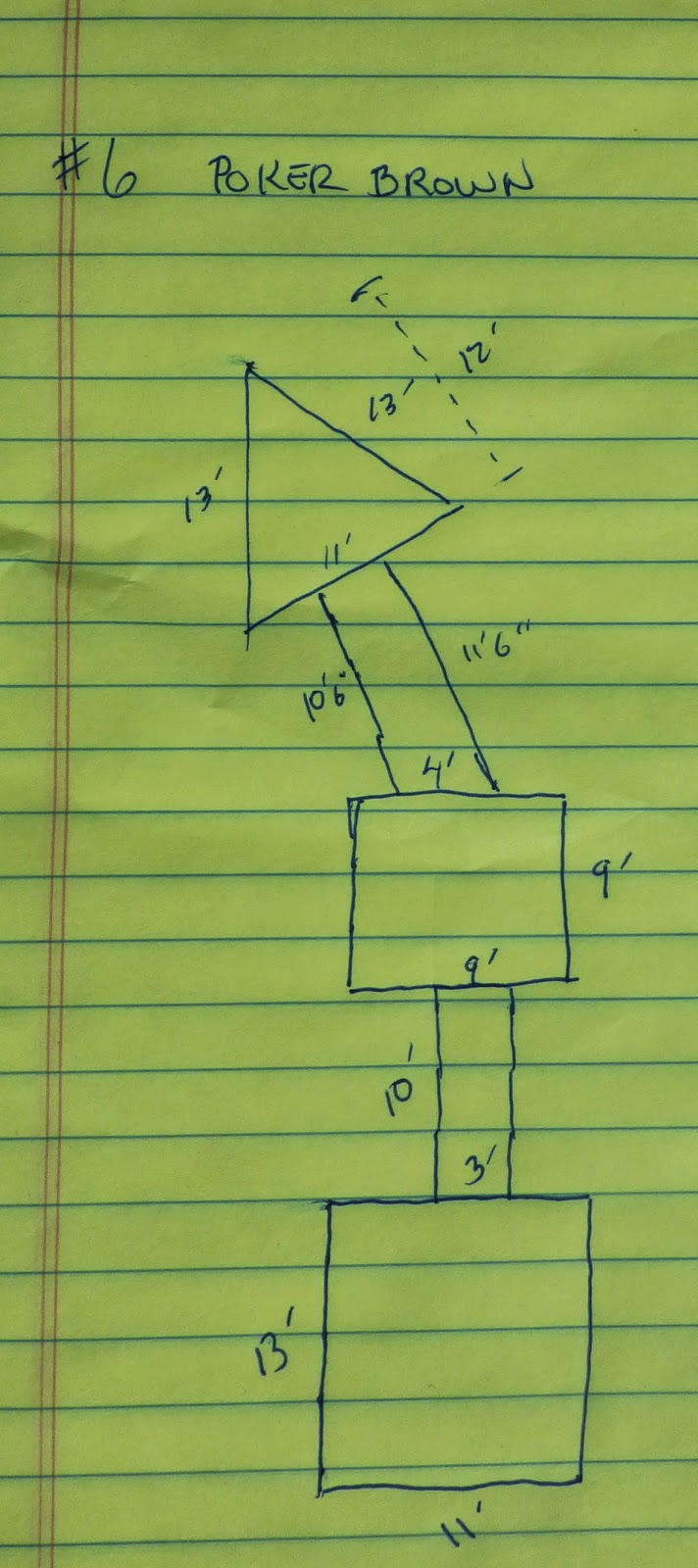

We sketched the thing and took measurements.

The arrows were constructed such that the point indicated

the easterly direction. The square

at the opposite end indicated west and usually supported the gas-powered

generator. A square in the middle grounded the tower.

We found that several of the old beacons arrows are located

near where present-day cell phone or other communication service towers have

been erected.

We found one example that was a challenge to get to but well worth the effort.

Silver Zone Pass is about ten miles west of Wendover,

NV. Hiking the service road seemed

smarter that trying to drive up there.

Along the way, we enjoyed an increasingly panoramic view out

toward the distant salt flats of Utah.

We find a nicely preserved example at the summit.

There is so much history to be

found. Some of it is granted

significance because of its role in binding the continent and securing our

nation like the Gold Spike National Historic Site. Others, like these crumbling arrows may soon be lost to time

and the elements, but they were no less important in binding together the

nation in their day.

o0o

Notes:

More information on the Beacon Arrows of the Early Air Mail

Service can be found on-line.

Here’s one pretty good source: http://sometimes-interesting.com/2013/12/04/concrete-arrows-and-the-u-s-airmail-beacon-system/

The FAA publishes many pilot and flight specific manuals. http://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/flight_info/avn/flightinspection/fihistory/

Buried in a section called “Flight Inspection History “ we find:

Drawing

upon the methods of marine navigation, airway beacons were developed by the

Post Office. The earliest lighting consisted both of rotating beacons and fixed

course lights. The beacons were placed 10 miles apart and the 1,000-watt lamps

were amplified by 24-inch parabolic mirrors into a beam exceeding one million

candlepower. They were mounted onto 51-foot towers anchored on 70-foot long

concrete-slab arrows, painted black with yellow outline for daytime

identification and pointing along the airway. Course lights were also mounted

on the light towers, projecting a 100,000 candlepower searchlight beam along

the airway course and flashing a Morse-code number between one and nine that

identified the individual beacon along a hundred mile segment of airway.

Intermediate landing fields were spaced every 30 miles along an airway. These

fields were primarily used for emergencies during poor weather or for

mechanical difficulties. Pilots could locate these intermediate fields at night

by green flashing lights installed on the nearest airway beacon.

The

transcontinental segment between Chicago and Cheyenne was equipped with the

beacons and nighttime service was begun on July 1, 1924. Additional segments

were lit both east and west and the entire route east of Rock Springs, Wyoming,

was lit by July 1925. Work continued to complete the lighting of the entire

route, and the segment between Rock Springs and Salt Lake City was lit in 1926.

The last segment over the California Sierras, with the most difficult terrain,

was not completed until 1929 and was done by the new Aeronautics Branch of the

Department of Commerce. As the airway was lit, the movement of airmail became a

viable service. Even with only the eastern two-thirds of the route available

for night flying, the mail could still move from San Francisco to New York in

29 hours, versus 72 hours for the routine rail service. By the mid-1920s,

airmail was the greatest success story of commercial aviation and became the

foundation upon which the passenger airlines were built.

Epilogue

“Oh, yeah, I knew about

those,” my 92-year old mother said while sitting in her rocker at the

independent living home. I’d just

informed her that I’d be seeking some long forgotten concrete arrows that were

once used by airmail pilots to direct their flights across the Utah and Nevada

desert. “Hap (her father) used them when he

flew the air mail after the war.”

“How come you never told

me?”

“There’s a lot I never

told you…”

Edgar W. “Hap” Bagnell was

an “Early Bird” having piloted powered aircraft prior to December 17, 1916: http://www.earlyaviators.com/ebagnell.htm. I was not aware that’d he’d flown

airmail after World War I until I mentioned the arrows to Mom.

© 2014

Church of the Open Road Press

You need to write a book! This would be so interesting. Actually, all of your post-retirement adventures are interesting.

ReplyDelete