A tale of either or

My transgression this day would be nothing compared to those visited upon this place a century and a half ago. The Bloody Rock trail is closed: I hiked on it anyway.

The Eel River commands the third largest river drainage in all of California. Several Native American groups called specific tracts of this remote, beautiful and largely overlooked region of the Coast Range home. Skirmishes and scuffles broke out from time to time, but rarely, historians report, were casualties massive. Issues related to territory developed only after European settlers found value in grasses for grazing cattle and sheep; and that damned gold a bit further north.

A trail guide informs me that the Bloody Rock trail is a 2.4-mile path linking the parking spot on 20N01 to a wide and cool Eel River.

Initially, the trail is a poorly used slit in a huge field of knee-high wild oat – it’s officially closed, after all. The seeds and stickers of these grasses lodge in my long pants.

Into and out of a stream course, I venture into the northern-most scar of last year’s Ranch Fire – the largest, acreage-wise, in California history. While I’m seeing the footprints of other transgressors who ignored the trail closure, I’m not seeing the outcrop. I’d read that the rock itself is a mere .5 mile from the trail head. Some 45 minutes on and descending to where I could hear the rapids of the Eel, I realized I’d missed a stitch along the way.

Mounting a hill, off-trail, I gain a view of the river canyon and see a rock outcropping, but at only about 20 of 30 feet in height – a jumper might end up with some bruises or broken a leg – it doesn’t look like my quarry.

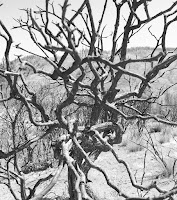

Backtracking, I figure I’ll need to engage in further book-learning and come back another time. Cresting a rise and looking through the scorched brush and naked oaks, a basaltic monolith appears to jut out from the edge of the ridge a few hundred yards west. I clamber off-trail to get a better view: Aha! Bloody Rock, just as it appeared in some old-time photos.

There’s a rugged little stream course between me and the rock; along with a field choked with wild oat and dense with spiny thickets eager to rip at my clothing and flesh. The fire-scarred ground beneath my feet is pocked with holes in which once grew oaks and digger pines; their stumps reduced to ash even well below the surface. Each hole is an ankle waiting to be twisted and I’ve only got two ankles. I’m hiking alone and it’s a mile back to the Subaru. This is why the Forest Service wisely closed the area.

Enough people died in these parts, I reckon, and after a couple of snapshots, I resume the trail and find my way back to the road. Any spur leading to the top of Bloody Rock must have been obscured with weeds, thus invisible to passers-by such as myself. My exploration was not a failure, this day, but it wasn’t a great success, either. I’ll return some spring when the trail is open, the grass green and the temps more moderate.

The story of Bloody Rock is this: In the fall or winter of 1859, deep in Eel River territory, a group of Yuki – self-exiled from the Round Valley Reservation – tried to befriend and enlist their ancestral foes, the Pomo, in common cause against what was perceived to be a bigger threat: the influx of whites. The Pomo rebuffed the offer and, in turn, shared their chumaia (enemies’) plans with the European settlers. The Americans sought to quell this insurrection and, according to Stephen Powers (1873?), chased the band the over the hills and through the Eel’s canyon, killing many. A group of 30 or 40 (some say about 65) took refuge atop a basaltic promontory overlooking the river. A dozen or so settlers cut off the Yuki’s retreat and…

“…Hemmed in on one side, headed off on another, half-crazed by sleepless nights and days of terror, the fleeing ‘savages’ did a thing that was little short of madness…”. They were offered three alternatives: “Either continue to fight and be picked off one by one, continue to truce, return to Round Valley and perish from hunger, or lock hands and leap down off the bowlder [sic]”

“They advanced to the brow of the mighty bowlder, joined hands together, then commenced their death song…” ultimately, “with one sharp cry of strong and grim human suffering,” leapt down to their death.

Source: Stephen A Powers, The Tribes of California,

originally published 1876 (?), page 138.

Quoted in: Frank Baumgardner Killing for Land in Early California,

Algora Publishing, 2006, page 259-60;

(out of print, but available to the persistent)

While websites such as Find a Grave suggest that “many years later the bones of the Indians were still in evidence at the bottom of Bloody Rock,” some others – archeologists and paleontologists – report that no such remains were ever found. It is known that none of these Yuki ever returned to the reservation at Round Valley leading to one of two conclusions. Either:

a) The Natives chose the course of the “noble savage” [that term from Powers] and engaged in mass suicide, or

b) The people were coaxed down from the rock and executed at various, undisclosed locations throughout the wilds of the Eel.

The former offers good theater; the latter, an example of how a culture of superior weaponry and technology can overwhelm and eradicate a culture with lesser tools. *

Notes:

The Church of the Open Road discourages folks from hiking on closed trails. I shouldn’t have engaged in this activity.

Although I chose to take the Subaru, the Mendocino National Forest maintains miles of delightful dual-sport and/or adventure touring roads: nicely graded, wide, gorgeous views and little traveled. Next time I’m bringing Enrico, the Yamaha.

Here is a link to a Bloody Rock Trail guide: https://www.alltrails.com/trail/us/california/bloody-rock-trail Their “getting there” tab serves as my “Today’s Route.”

Here is a link to the “Find a Grave” listing of Bloody Rock: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104167874/65_yuki_indians-killed_at_bloody_rock

* This little journey prompted me to ask myself: As human history repeats and repeats itself, is it any wonder that countries like Iran and North Korea seek membership in the club of nations armed with nuclear weaponry?

© 2019

Church of the Open Road Press