…with the San Andreas Fault thrown in to boot!

Cresting a pass in the Temblor Range, the vast expansive valley of a once-inland sea spread out before us. Miles off, the far ridge, dappled by a low early morning sun, displayed patches of bright and shadow. Breath-taking! The golden yellow swaths seemed almost neon – almost too intense to be an image created by early morning rays. And it was 10:00 AM, well past early morning. And it was slightly overcast.

|

| Some of these pictures, I'll modestly suggest, are worth clicking on to expand. |

My only previous visit to the Carrizo Plain National Monument came in a December a few years back. In the midst of California’s five-year drought, there’d yet to be much winter rain. The ground was dry and my interest bounced between the ridgelines and peaks of the Temblor Range to the east and the Caliente Range to the west; and the derelict farm implements, a rusting display of a short span of the plain’s history.

My gray-scale memories of the region beckoned me to return on a day like this one would be.

Here are a few shots that, frankly, fail to capture the explosive colors we would see this day…

Even before we made our way onto the Carrizo Plain, we found ourselves stopping along CA 58 to capture springtime scenes that in perhaps two more weeks would be gone.

At the junction of CA 58 and Seven Mile Road we hung a left, and then an immediate left onto Elkhorn Road. Elkhorn Road is named for the Elkhorn Scarp, a geologic feature created by movement along a faultline.

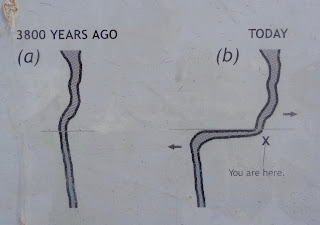

David Lynch’s Guide, referenced below, reminds us to stop at Wallace Creek where a hike up the hill takes us to active evidence of the San Andreas Fault. An interpretive sign illustrates the northwesterly movement of the Pacific Plate and its impact on the stream course of Wallace Creek.

The North American Plate is to the left in this frame which is shot from the Pacific Plate side. This fifty-yard section runs roughly north south. You can see where Wallace Creek comes in from the east.

Behind me, the creek takes another abrupt turn heading west toward the plain. This is as good a view of an offset creek caused by tectonic forces as can be found anywhere in the world.

We follow Elkhorn Road round a bend to find a landscape of hillsides painted in wildflowers.

Fast-forward to later in the day: This is a shot looking east toward the Elkhorn Scarp and the Temblor Range.

On this day, we saw little evidence of wildlife, although since the week-ago rains, more than a few little someones had darted across the area.

I’m glad the sandstone paw print turned out as well as it did. My prowess for close-ups of flowers with my new Panasonic leaves much to be desired.

I’m sure travel partners David and Carol were much more successful because they’re both much more patient with their cameras.

I did get lucky once or twice…

…and I did luck out with this little beetle. Many of his buddies could be found in and about burrows dug by unseen rodents.

Until I gain better command of the camera, I’ll need to be content with distant shots of carpeted lowlands…

…and hillsides.

At the south end of the scarp, we make a choice to climb over a ridge and descend onto the Carrizo Plain proper. Along the way a hazy view of the southern San Joaquin invites pause.

Heading north on Soda Lake Road, we are reminded of the ranching heritage that dates from the early 20thcentury…

…through early mechanized times.

Impressive is the gentle beauty of plain’s floor where in one section the flora will be of one sort and two hundred yards further on, something entirely different.

Makes me wish I knew more about botany.

The Carrizo Plain, bounded on the east by the Temblor Range, the west by the Caliente and the south by the Transverse, was once a great inland sea. Precipitation falling across the area would flow into a basin that had no natural outlet.

A boardwalk crosses the marsh, but we chose short climb to a lookout point where what’s left of that inland sea – Soda Lake – spread out before us.

Also, before us lay this swath of blue explored by a couple of fellow sojourners.

Too soon, we were on the road exiting this marvelous and relatively undiscovered corner of California. I left delighted that I’d made this return trip, thinking that I’ll need to come again, once I’ve figured out my camera.

Any excuse will do.

o0o

Notes and Resources:

Field Guide to the San Andreas Fault by David K. Lynch: Thule Scientific, Topanga, © 2006 & 2014. $40. Get this while it can still be found! Lynch provides insight into the geomorphology of the entire San Andreas rift from Brawley in the south to Cape Mendocino in the north. Lynch provides mile-marker-by-mile-marker highlights divided into 12 day trips where the reader/adventurer can spot evidence of one of the more dynamic aspects of California’s fluid geography. His trip six – Soda Lake Road to Simmler – served as a guide for our sojourn. Lynch recommends devoting a whole day to this remote region. We did.

Peterson Guides: We carried A Field Guide to Pacific States Wildflowers and Rocks and Minerals as well as a bird book but found that with so much to see and with so many stops to view both flowers and the fault zone, we rarely referenced them. Still, they were good to have along and it felt good to find a photo of some rusty colored sandstone that matched the bit I’d pinched between my fingers.

The Bureau of Land Management offers this link: https://www.blm.gov/visit/carrizo-plain-national-monument I’d urge readers to check out this site, bearing in mind the cautions and regulations contained here-in.

Carry water!

o0o

Today’s Route: From Buttonwillow on I-5 exit CA 58 west through McKittrick – lots of oil extraction in the area, but, curiously, NO GAS available – and over a pass in the Temblor Range toward California Valley. Left on Seven Mile Road (unpaved); almost immediate left on Elkhorn Road (also unpaved). Essentially on top of or near the fault, follow Elkhorn Road a distance we neglected to measure (nearly 30 miles) to a junction found just as you enter a mountainous region to the south. Bear right and climb steeply over the range making sure you pause for a grand view of the southern San Joaquin Valley before descending into the plain.

Turn right onto Soda Lake Road (mostly unpaved) and travel north-northwest to Seven Mile Road. Head east to complete the loop.